It’s a Bird, It’s a Plane, It’s Space Junk

- By Stefan Hammond

- February 13, 2023

Recent news cycles crackle and hum with stories about fighter jets versus mysterious flying objects. Here's one: in early February, the U.S. Space Force announced that “a U.S. Air Force fighter safely shot down a Chinese high-altitude surveillance balloon.

The USSF statement explained that the mystery dirigible was fired upon “as soon as the mission could be accomplished without undue risk to us [sic] civilians under the balloon's path," said a senior defense official speaking on background. "Military commanders determined that there was undue risk of debris causing harm to civilians while the balloon was overland"."

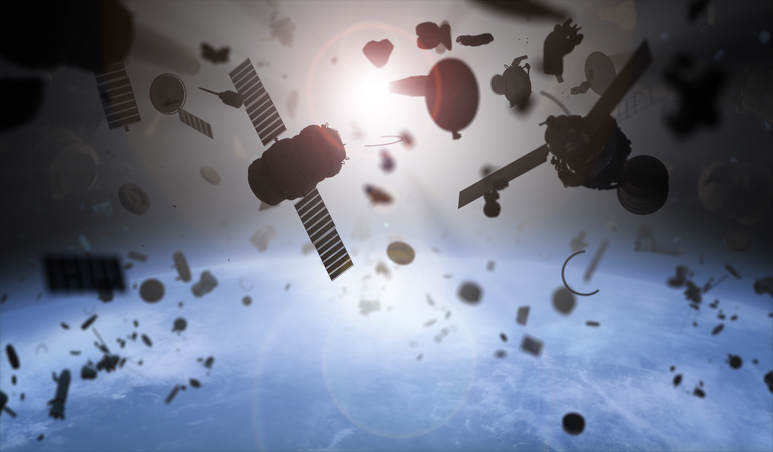

But there's a grimier reality orbiting the planet: a collection of objects colloquially known as “space junk.” And it's a motley lot of celestial detritus.

Space debris is a hodgepodge of “defunct human-made objects in space—principally in Earth orbit — which no longer serve a useful function.” It's waste material from our space efforts dating back to the original Sputnik 1, which was “launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union [in] 1957 as part of the Soviet space program.”

And in 2023, Russia (the former Soviet Union) again hit the space junk headlines with Cosmos 2499.

Enigmatic satellites

“A Russian satellite known as Cosmos 2499 (sometimes referred to as Kosmos-2499) has broken up in orbit,” wrote Amanda Kooser in a February CNET story, “creating dozens of new pieces of debris.”

No one seems to know why Cosmos 2499 disintegrated. “Cosmos 2499 was an enigmatic satellite,” wrote Kooser. “Russia quietly launched it in 2014 with an unknown purpose.”

A motley lot of celestial detritus

“The purpose of Cosmos 2499 is not known publicly, though it was launched alongside other Russian military communication satellites,” said Canada's Global News. “The secret satellite recently broke into 85 pieces and will pose a debris hazard for at least a century,” said Popular Mechanics.

The “Object E” satellites

Cosmos 2499 was preceded by Cosmos 2491 in 2013 and post-ceded by Cosmos 2504 in 2015—a group of satellites launched from a base in northern Russia. “Known as ‘Object Es’ as they were the fifth object cataloged from these launches in addition to the upper stage and three communications satellites,” said Ars Technica. “However, it is not entirely clear what the purpose of these satellites is or to what end the Russians aim to use these rendezvous and proximity operations.”

Can we stop LEO from becoming a demolition derby?

We can presume that their purpose was not to crash into other objects, but that doesn't seem to have been the case — either in the recent incident or 2491's 2019 shedding of an estimated 20 pieces of debris. “Brian Weeden, an expert in space debris at the Secure World Foundation who has studied the Object E satellites, said he did not think the debris-shedding events on both Cosmos 2491 and Cosmos 2499 were caused by collisions in orbit,” said ArsTechnica. “Rather, they appear to be part of a repeating pattern.”

"'This suggests to me that perhaps these events are the result of a design error in the fuel tanks or other systems that are rupturing after several years in space rather than something like a collision with a piece of debris'," Weeden said.”

Weapons testing in space

In November 2021, another Russian satellite posed a problem to the International Space Station. “Early on November 15 astronauts aboard the International Space Station received an unexpected directive: Seek shelter in your docked spacecraft in case of a catastrophic collision,” wrote Nadia Drake in National Geographic. “The station was about to pass through a freshly created cloud of orbital debris that posed a significant risk to the seven space travelers on board.”

This debris threatened the lives and well-being of seven people, not to mention the ISS. “Four NASA astronauts, who had arrived just last week, retreated to their SpaceX Dragon capsule, while Russia’s two cosmonauts and another NASA astronaut took cover in their Soyuz spacecraft,” wrote Drake. “They stayed inside these orbital lifeboats for about two hours, then repeated the exercise roughly 90 minutes later, as the station again passed through the new debris cloud.”

What happened? “The U.S. State Department later confirmed that the debris endangering the space station was produced when Russia tested an anti-satellite (ASAT) weapon and intentionally destroyed one of its own defunct satellites,” said the National Geographic story. “The test shredded a satellite whose orbit intersects with the path of the ISS, putting the humans on board, including Russian cosmonauts, at risk.”

While it seems cavalier to fire weapons in space and blow stuff up, even if it's one of your defunct satellites, humans all too often treat space junk as something trivial. “Things were simpler half a century ago, when there were only 10 space-faring countries, and distances in outer space were so infinite that the dangers of a collision were infinitesimally small,” said Asia Nikkei. “Today, there are nearly 90 countries with a presence in space.”

Orbital congestion

Contributing to this glut of satellites is SpaceX, which was “founded in 2002 by Elon Musk with the stated goal of reducing space transportation costs to enable the colonization of Mars.”

Starlink “is a satellite internet constellation operated by SpaceX [and] providing satellite Internet access coverage to 48 countries.”

How much manmade material is Starlink putting in orbit? As of February 2023, “Starlink consists of over 3,580 mass-produced small satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO)...nearly 12,000 satellites are planned to be deployed, with a possible later extension to 42,000.”

“Astronomers have raised concerns about the effect the constellation can have on ground-based astronomy and how the [Starlink] satellites will add to an already congested orbital environment.”

Space force: nice logo

Despite their spiffy logo, which should appeal to fans of Star Trek, the U.S. Space Force seems unable to offer any solutions to the problem of space debris.

“Space congestion and space junk are becoming a serious global problem and a potential flashpoint for international conflict,” wrote Forbes Magazine in a 2021 article. “But publicly at least, America’s defense establishment in general and U.S. Space Command, in particular, can do little about it.”

The Forbes story says: “It’s a scenario retired NASA senior scientist Donald Kessler predicted in the 1970s: As the density of space junk and vehicles goes up, a cascading cycle of debris-generating collisions can arise that could make LEO too hazardous to support most space activities.”

Which begs the question: is it already too late to stop low-earth orbit from becoming a demolition derby of viable and defunct satellites?

Stefan Hammond is a contributing editor to CDOTrends. Best practices, the IoT, payment gateways, robotics, and the ongoing battle against cyberpirates pique his interest. You can reach him at [email protected].

Image credit: iStockphoto/Petrovich9